These days, it’s somewhat difficult to define what “luxury” is. Our parents and grandparents used to have some idea; “luxury” was anything you bought that wasn’t an essential expenditure like food, basic clothing, electricity, heating costs, and so on. We used to define luxury as anything we bought which we wouldn’t suffer from a lack of.

However,, we can usually have a thing as and when we want it. And we’re often impatient. Our daily lives contain luxury, lots of luxury, even and especially luxury that we haven’t paid up front for and have bought on financial credit. The BBC journalist Alistair Cooke, who travelled between Britain and America through his whole life, used to tell the story of Frederic Tudor, one of the first pioneers of consumerist ambition in the new nation of America in 1784. Tudor “became a merchant, and an inventor with so many mad ideas that didn’t pay off, that a whimsical brother wondered why he didn’t break up the ice on the Boston ponds and ship it to the tropics”. “The youngest Tudor”, Cook tells us, “ignored the crack and seized on a brain wave.” “He shipped one hundred and thirty tonnes of ice to Martinique.” Tudor “made ice a necessity, even – at the end of the Second World War – in England”. “Luxury” isn’t about fulfilling a need; it’s about creating a need which people never even knew they had inside them then fulfilling it. There’s a big difference.

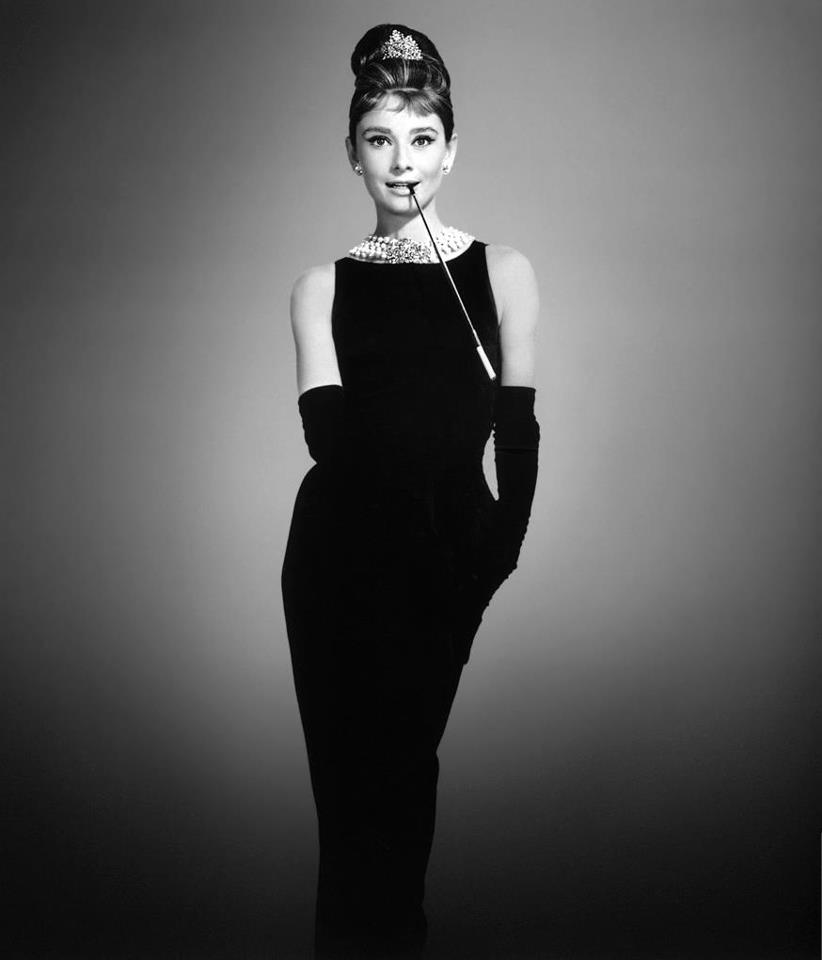

There’s also a difference between luxury and excess, especially in a recession. If you don’t design a product with a certain elegance in mind, then it’s just ostentatious. And that’s a square that designers are always trying to circle. We have two criteria for a luxury product — it needs to activate a need which people didn’t already know they had, but it needs to be an example of elegance and class as well. Fashion is the ideal medium for a luxury item in the current economy. Even if it means we need to scrimp or save in other areas, we still ensure that we’re wearing something we feel comfortable and stylish in, wherever we are and whatever we’re doing. The “Audrey Hepburn dress”, or the little black dress, is always the best expression of that kind of fashion. The “Audrey Hepburn dress” is something no self-respecting woman would pass up the opportunity to own. It positively screams elegance.

From its earliest beginnings (which were with Coco Chanel in Paris in the 1920s), the little black dress was explicitly designed to be a luxury item, to radiate all the connotations of luxury. But what burning “need” does the “Audrey Hepburn dress” activate for the women who choose to wear it?

In the modern economy, everything can be cheaply made. We can wear a completely different wardrobe every single week if we want to, because a cheap version of almost anything is available at the budget shops. It’s exactly for this reason that the “Audrey Hepburn dress” is so important.

The “Audrey Hepburn dress” is luxurious because to own one and wear it proudly is in some ways a rejection of ostentation. As Yves Saint Laurent told the designers he employed, “Fashion fades, style is eternal”. By owning a fashion piece that cuts against the relentless need to keep buying cheaply-made and cheaply-branded clothes, your wardrobe contains a statement against the version of luxury which some people associate with “conspicuous consumption” — spending lots and lots of money to prove your social value. Owning a piece of timeless quality strikes out against the tendency of the modern economy to over-produce everything. Over-production comes at the expense of quality and the working standards at the heart of production.

However, though an “Audrey Hepburn dress” means the owner is striking out in this bold and daring way, it’s also cleverly designed to give its target consumer market the inner need to make more buying choices like this. In other words, the dress both convinces its owner that buying luxury is not ostentatious and convinces them to buy more luxury items with this same mindset.

When Coco Chanel designed the little black dress in the 1920s, she was consciously trying to rehabilitate the French economy by giving people “luxury” items they could trust and believe in. With European economies on the slide after the expenditures of the 1914-1918 war, people were desperate. People needed luxury. The “Audrey Hepburn dress” epitomised the needs of women to feel good about themselves again, but it did so by defining luxury as simple, one-off purchases, rather than excessive overspending. The little black dress also activated something in the French psyche. It activated an innate desire to continue to be able to tell the difference between what Saint-Laurent labelled “fashion” and what he labelled “style”; that’s some achievement for one simple fashion piece.

For a luxurious take on the little black dress, that’s both luxurious and ethically-produced see Duchess London’s interpretation. Their “My Fitting Room” service also allows you to experiment with the peace and security of knowing that you can send unwanted pieces back.